If you still have doubts about climate change, ask a wine producer, young or old, what they think. You’ll quickly get an answer. Today, viticulture has become a combat sport, and things inside the bottle are no less challenging. The differences in quality between regions, estates, and even within the same estate have never been so stark. Say goodbye to the old vintage charts by region, which still appear in many so-called "reference" guides. While such charts might have previously been seen as reflecting trends rather than absolute truths, today, relying on the year alone to find a good wine deal is no longer an option. A vintage rated 12/20 can be just as valuable as one rated 18/20, especially if the rating applies to the entire French wine industry! (We get this spiel every year on the 8 p.m. news!). Yes, you read that right: there are now as many risks and advantages in buying wine from a lesser vintage as from a great one.

The causes are complex, multifaceted, and sometimes contradictory. Let’s take a moment to consider the uncertainty surrounding what we initially deem "successful" vintages.

We often hear about "winemaker vintages" when the year has been difficult. By "difficult," think hailstorms, rain, lack of ripeness, or reduced yields. From now on, we might need to use the term for so-called "easier" years—those with plentiful, well-ripened grapes—because microbiological balances are becoming increasingly difficult to manage. Volatile acidity, volatile phenols, geosmin, mousiness, capricious fermentation, unexpected vegetal flavors, unstable color—these issues can add up and affect all categories of wine, from easy-drinking to structured wines, from sulfite-free to “conventional” wines. And unfortunately, no region or winemaker, no matter how skilled, is immune.

What does this mean? What should we make of a year that seems good at first but turns out inconsistent later? If "bad" years have almost disappeared and "ripe" years are nearly guaranteed, perhaps a "successful" year—defined as one without microbiological complications—will become the new marker of a great vintage. In other words, a year without trouble.

To be clear: this isn’t about assessing the variability between estates or regions. It’s about rethinking how we evaluate wines beyond simple ripeness, clumsily summed up by a score in outdated vintage charts.

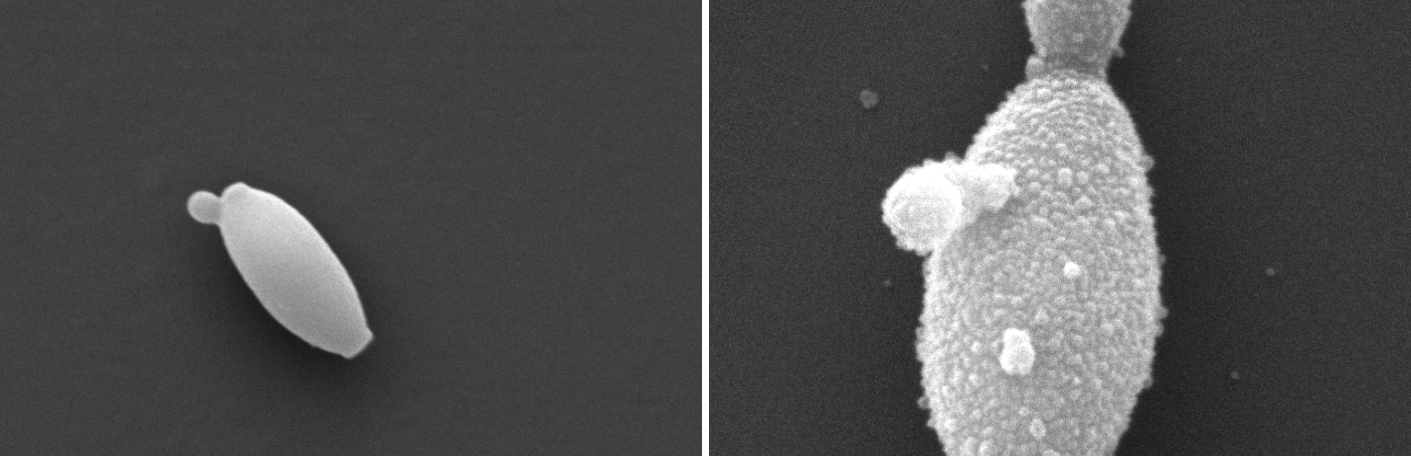

First potential cause of these issues: the microbiological changes resulting from both natural and artificial alterations in the vineyard ecosystem and winemaking techniques. To understand their effects, we must shift perspective—from the infinitely large to the infinitely small. Gone are the days of casual tastings; now, we must taste with acute precision. The question is no longer whether the wine is drinkable—most are—but whether it is “successful”: precise, pure, and refined, capturing only the essential message of the vintage, and certainly not its scars. Whether it’s a carbonic wine meant to be consumed within a year or a Grand Cru built for eternity, wine can no longer settle for being a “good compromise,” because the means to “do better” are available and accessible to most in both technical and financial terms.

Some might argue that certain wines have embraced the opposite direction—randomness and imprecision—with some commercial success. However, these represent a minority, negligible in volume and market share, and sufficiently marginal for us to focus here on the majority of wines consumed, whose quality and consistency deserve rethinking.

In this respect, oenology has its work cut out for it. It must adapt to the vintage, tailor its approach, account for living systems, and stop elevating its discoveries into universal systems or its solutions into cookie-cutter recipes. Some laboratories have already understood this; most have not yet. It’s an exciting time for the science of wine, provided it is willing to shift its paradigm and recalibrate its value system.

As for the winemaker, their craft is becoming infinitely precise. It already was, of course; we all know that great wines are made in the details. But now, those details are examined under a microscope or with a gas chromatograph, with the help of specialists both in the vineyard and the cellar, and with the guidance of critics who are increasingly demanding because, by definition (we hope!), they are ahead of their time—and not merely followers of passing trends.

A winemaker recently told me he was replanting high-yield rootstocks while reducing planting density to counteract the concentration of grapes caused by climate change and lower the pH (a concern for wine stability). Another said he was returning to tangential filtration to avoid “issues.” Yet another mentioned going back to using the concrete tanks his grandfather had used, once again for hygiene reasons. All of them claimed, for different reasons, that these changes were part of a cyclical phenomenon. We went too far. Now we’re going back to the old ways.

I think these winemakers are mistaken—at least in their conclusions. This is not a cyclical phenomenon in which history repeats itself. In truth, history does not repeat itself. It only seems to, because the solutions being adopted now sometimes resemble those that resolved entirely different issues in the past. For instance, the use of high-yield rootstocks in the 1970s has nothing to do with the context described earlier.

In many ways, the role of the winemaker has evolved. And the role of the true winemaker—one removed from entrepreneurial concerns—has primarily undergone a shift in its value system. For example, harvest decisions are no longer based solely on yield or sugar-acid balance, which are “coarse” and easily measurable metrics. Now, they must also consider the vineyard’s redox balance, VBNC (viable but non-culturable microorganisms) counts, and other such meticulous data—information that remains too rarely quantified.

Does this seem far removed from the craft of winemaking? Or reserved for an elite? You’d be both right and wrong. You’d still be right today, but certainly wrong tomorrow—especially in the context of climate change. It is now these infinitely small details that drive the most significant differences in quality.

The old markers of “poor” vintages or “ripe” vintages are giving way to new criteria at the grape level rather than the vineyard level. These demand the same rigor and meticulousness as before, but at far greater levels of sensitivity, knowledge, and expertise.

Ultimately, rather than a cycle perpetuating the illusion of an eternal return, let us prefer the idea of a fractal pattern—one that exhibits a similar structure at every scale. In this way, a fractal viticulture would be one where principles remain the same but are applied at greater depths—that is, at levels of understanding capable of appreciating the complexity of living systems, anticipating their evolution, and, more broadly, uniting the wine industry, legislators, and enthusiasts around environmental and ecological projects. These projects are often misunderstood because they are presented superficially, without the necessary depth.

Fractal wine, in turn, would be the product of this deep refinement, preserving only “what matters.” This is not about an oenological purification that inevitably leads to aesthetic sterility, nor an overly purist oenology that ends in philosophical naivety or blissful totalitarianism. Instead, it is about a fertile oenology—one that is open to learning from living systems without either submitting to or opposing them.

As for critics, their role must remain that of a bridge—connecting up-to-date scientific knowledge with a cultural and aesthetic heritage rooted in history. Critics must avoid succumbing entirely to either realm by embracing a fractal approach to tasting—an intricate appreciation that accounts for the whole. This is what we strive for in our tastings and, in a different form, in our publications.

This is certainly what we try to do in our tastings, but also, in a different form, in our publications. No vintage charts at La Tulipe Rouge, but selections of 'successful' wines and articles that delve deep. Starting with the interview of our taster and microbiologist Gilles Martin, who talks to us with passion and humility about the infinitely small. On the domain side, we invite you to rediscover Mas Amiel, whose philosophy, relationship with the living, and great technical mastery have never been so fractal! Finally, on the tasting side, what better example to illustrate fractal wine than Château-Chalon! From afar, oxidized wines (how many oenologists have I heard say that about these wines!), but up close, in the intimacy of the senses and the living, national treasures to rediscover in this new year. Best wishes and happy reading.

Olivier Borneuf

**These are defects that alter the taste, flavors, and sometimes the aging potential of a wine.

***VBNC (Viable But Non-Culturable) refers to microorganisms that are alive but not culturable. These microorganisms are in a state of very low metabolic activity but remain viable and can become culturable when placed in a more favorable environment.