Some time ago, the Château-Chalon AOC had the brilliant idea of organizing a tasting of wines from the appellation's producers, spanning an extensive period from the 2016 vintage to the 1964 vintage. A marvelous moment of sharing and emotion, offering us the perfect opportunity to revisit this exceptional wine: the renowned vin jaune of Château-Chalon.

Château-Chalon is far too grand a wine to be captured in a single article. Did not the prince of gastronomes, Maurice Edmond Sailland, known as Curnonsky (1872–1956), rank it among the five greatest white wines in the world, alongside Château d’Yquem, Coulée de Serrant, Montrachet, and Château Grillet? What approach could best celebrate the greatest of vin jaune wines? Its history? Its vineyard? Its grape variety? Its producers? Or perhaps a little of all these? Any one of these topics would warrant an entire volume, while a mere sketch of the whole would fail to convince even the most indulgent of connoisseurs.

In truth, all great wines have a story, and Château-Chalon’s is no less extraordinary. All great wines are rooted in great terroirs, and Château-Chalon’s vineyard is no less spectacular. All great wines are associated with one or more outstanding grape varieties, and Château-Chalon is inseparable from the marvelous Savagnin. Lastly, all great wines owe their existence to great producers, and those of Château-Chalon are worthy of the formidable legacy they carry. Ultimately, to truly understand Château-Chalon, one must look beyond the obvious—without neglecting the essentials—delving into the details where the self-evident hides the most beautiful of secrets. This secret, often taken for granted but key to the miracle and excellence of Château-Chalon, lies in the voile (veil). Before we dive into the mysteries of this remarkable layer of flora, let us take a brief journey through the historical, geomorphological, and ampelographic singularities of the greatest wine of the Jura. These elements are deeply intertwined with the unique characteristics of the voile of Château-Chalon. We shall conclude this overview with our selection of standout cuvées from the magnificent tasting.

First of all: What is a vin jaune?

Vin jaune is a wine typical of the Jura region, made exclusively from the white Savagnin grape variety. After completing alcoholic fermentation, followed by malolactic fermentation (though this step is not mandatory) and racking, the wine undergoes a minimum aging period in oak barrels. During this time, the barrels are not topped up, leaving space for a natural yeast layer (voile or flora) to develop on the wine’s surface. This voile protects the wine from oxidation while imparting its distinctive aromas of walnut, spices, and curry. The aging process continues until December 15th of the sixth year following the harvest, with at least 60 months spent "sous voile", allowing the wine to acquire its characteristic "goût de jaune" (yellow taste). The wine is then bottled in a specific vessel called a clavelin, which holds 62 cl. It becomes available to consumers starting January 1st of the seventh year after the harvest. Four appellations in the Jura are authorized to produce vin jaune: Arbois, Côtes-du-Jura, l’Étoile, and, of course, Château-Chalon.

The history

The vin jaune

There is tangible evidence of the existence of a vin jaune from Arbois dating back to 1774. However, if one adheres to the rigor required by historical research, it must be acknowledged—at least for the time being—that there is no specific date or location tied to the invention of vin jaune.

That said, from the 17th to the 18th century, Europe underwent significant historical transformations that profoundly impacted the dietary systems of its people. The discovery of the Americas, the conquest of the oceans, the adoption of new staple crops, the arrival of coffee, tea, and chocolate, coupled with the dramatic increase in sugar production and consumption, as well as the Reformation—which introduced greater diversity in culinary practices—all contributed to a complete upheaval of notions of indulgence, nutrition, and, more broadly, the ways Europeans ate and drank. It is difficult to imagine that wines remained unaffected by such profound shifts.

Indeed, the early 18th century saw the emergence of new, refined wines, somewhat breaking with the quality wines that had preceded them within the same vineyards. Examples include Tokaj in Hungary, Port in Portugal, Sherry in Spain, Marsala in Sicily, and Champagne and Sauternes in France. By the mid to late 18th century, regarding the renowned 1774 vintage, several accounts from owners of vin jaune, passed down through oral tradition, leave little doubt about the mastery of its production techniques. This suggests that the 1774 vintage was indeed the culmination of several decades of refinement by a handful of producers with the financial means to perfect such an exceptional wine.

Bottle of Arbois 1774 – © Serge Reverchon / CIVJ

The vin jaune of Château-Chalon

As for its birthplace, all indications point toward the village of Château-Chalon. Here are a few well-known quotes that dispel any lingering doubts about the probable origin of vin jaune. The esteemed jurist and erudite historian François Ignace Dunod de Charnage, writing in 1750, noted that, compared to Arbois, Château-Chalon’s wines, when “very old,” possess a distinctive taste “that is not unpleasant,” thereby implicitly acknowledging Château-Chalon’s precedence in the conception of vin jaune. More definitively, Paul Rouget in 1881 referred to “vin jaune or Château-Chalon wine, a very remarkable wine,” followed by the decisive observation that it “remains in barrels for fifteen, twenty years, and even longer, without topping up.” Lastly, let us not forget the oft-cited abbesses of Château-Chalon who, by the late 17th century, had likely begun crafting the renowned wine. It is therefore difficult to attribute a singular “Dom Pérignon” to the creation of vin jaune. Rather, it seems likely that several local initiatives contributed to the development of Château-Chalon’s vin jaune, which remains a wine unlike any other.

The vineyard of Château-Chalon

In 1935, Maurice Marchandon de la Faye referenced an old text about the Château-Chalon vineyard: “Take a step to the right or left, and the marvel ceases to exist; transplant, graft, or layer the vines to expand the vineyard, and you will fail to reproduce the miraculous transformation that occurs just 100 meters away in the original vineyard. The small hillside keeps its secret.”

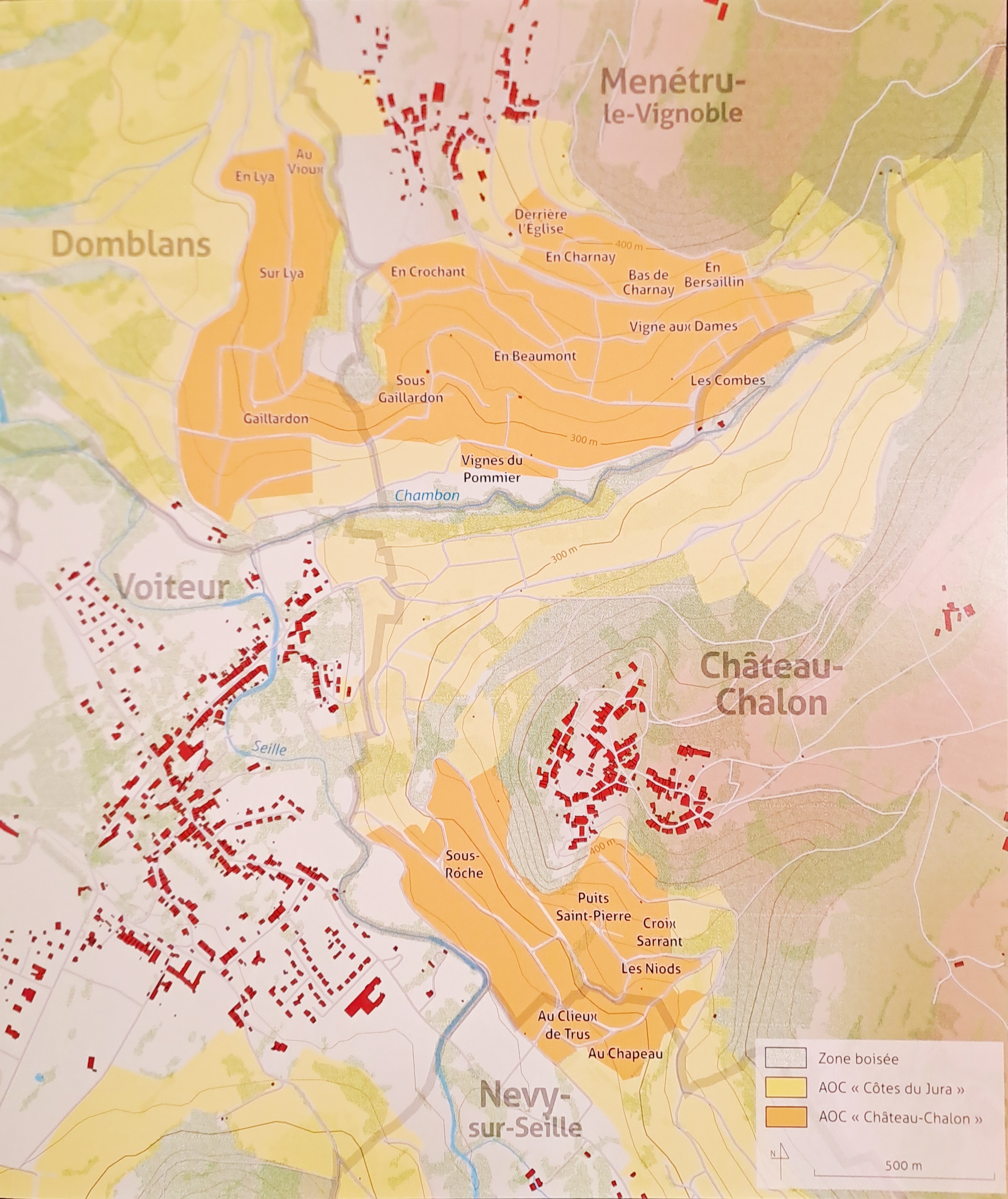

Nestled in the heart of the Jura, Château-Chalon is not just a picturesque village but also the appellation d'origine contrôlée (AOC) of an exceptional vin jaune. This unique vineyard spans only 56 hectares (62,8% of the AOC surface), representing a mere 0.02% of the Jura's total vineyard area. It is spread across four communes: Château-Chalon (12,33 ha), Domblans (13,6 ha), Menétru-le-Vignoble (26,8 ha), and Nevy-sur-Seille (3,27 ha). These communes belong to the Revermont natural region, which forms the western edge of the Jura Massif.

The vineyard is geographically bounded as follows:

To the east, by the first limestone plateau, with an average altitude of 550 meters.

To the west, by the plain that marks the eastern edge of the Bresse graben.

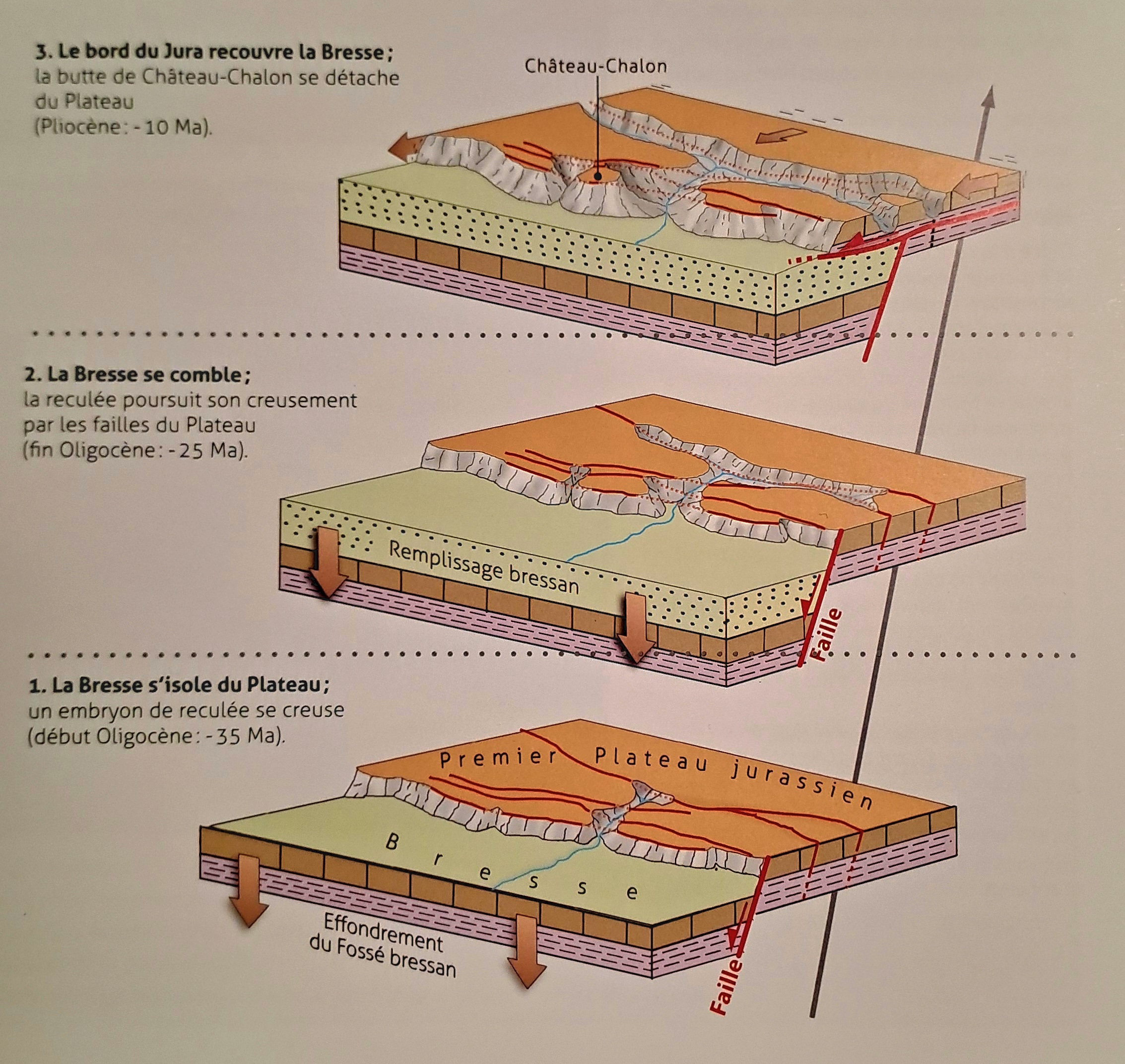

The formation of the reculée of Beaume-les-Messieurs - © Michel Campy

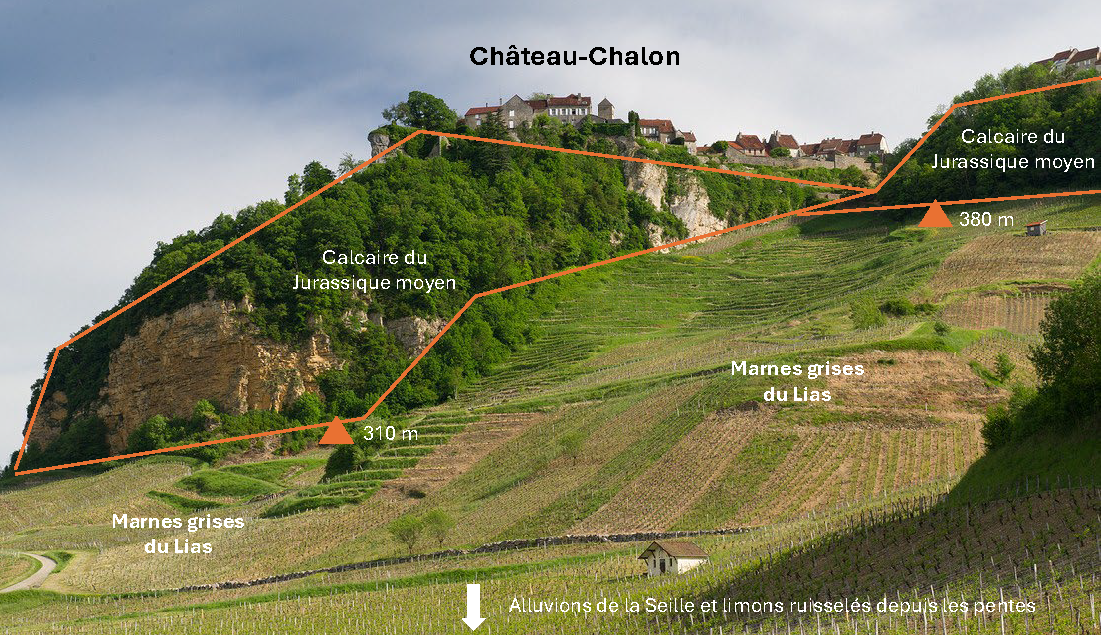

The plots designated for grape harvesting are situated on the slopes of gray marl (clay limestone) from the Lower Jurassic, dominated by the prominent yellowish limestone cornice of the Middle Jurassic. This cliff generously provides limestone scree that enriches and lightens the underlying marl. The vineyard is located at an altitude ranging between 250 and 400 meters. The south to southwest orientation of the slopes offers optimal sunlight exposure and excellent protection for the vines from cold north or northeast winds.

Geological presentation of the vineyard from the village of Château-Chalon

The region benefits from a semi-continental climate with oceanic influences, bringing frequent rainfall throughout the year and variable weather (of the 1189.5 mm of annual precipitation recorded in Lons-le-Saunier, 613.4 mm fall between April and September). The semi-continental character is marked by significant monthly temperature fluctuations, cold winters, and summers that are warmer than those on the oceanic coast, occasionally accompanied by severe storms.

Thus, the specific characteristics of each plot are crucial for achieving optimal ripeness of the white Savagnin grape variety:

Sheltered slopes, some with inclines reaching 45%, naturally drain excess water and maximize sun exposure.

The layered nature of the marl aids in deep water retention.

The cliffs shield the vineyard from cold winds from the north and east while retaining heat.

Regarding the marl, at least three types of terroirs can be identified:

Gray marl, which can be either "plastic" (e.g., the lieu-dit "Vigne aux Dames") or laminated schist (e.g., the lieu-dit "Puits Saint-Pierre"). On steep slopes, this marl is often near the surface and prone to water erosion.

Weathered marl (e.g., the lieu-dit "Gaillardon") on gentler slopes. These soils are naturally thicker, generally less clayey, and always carbonate-rich (with a basic pH).

Marl scree (e.g., the lieu-dit "En Beaumont"), which is relatively rare. The diversity of this terroir depends primarily on the thickness of the scree layer as well as the nature and size of the stones.

To attribute a distinct “taste” to each terroir would be to overlook the influence of numerous factors, such as the quality of the plant material, viticulture practices, harvest date, winemaking, aging, and, most importantly, the sensitivity of the producer. In the final analysis, the producer's interpretation of the site is undoubtedly the most significant factor.

An AOC of excellence

The grape variety savagnin blanc

The grape variety of the AOC Château-Chalon is primarily, and today exclusively, the white Savagnin. "Primarily," I say, because in the 19th century, another variety, the Bargine, was also present, though in small quantities. Known as the "Hungarian plant," it may correspond to the famous Furmint of Tokaj, though nothing confirms this.

Like all grape varieties, Savagnin blanc has its synonyms: Heida or Païen in Switzerland, Fromenteau in Haute-Saône, Formentin in Hungary, and Savagnin jaune, vert, or naturé in the Jura (names reflecting the clonal variations within the variety). It’s worth noting that Savagnin rose and Gewürztraminer are two varieties that have mutated from the Savagnin blanc.

According to genetic studies conducted by the INRA of Montpellier and the Vassal Estate (which houses a unique collection of Vitis vinifera varieties, interspecific hybrids, rootstocks, and wild vines of the Vitaceae family), Savagnin blanc has undergone very few cycles of hybridization and evolution, making it closer to the original wild vines, such as Vitis sylvestris. Today, it represents about 1500 hectares worldwide (in Switzerland, Germany, Austria, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, and Australia), with only 60 hectares in Château-Chalon.

With low to medium yields, well suited to cool and humid climates, and resistant to winter frosts, the Savagnin blanc thrives in marl soils (although results obtained on other soils in Australia demonstrate good adaptability). Moreover, it is highly resistant to grey rot due to its thick, robust skin. In winemaking, it is capable of producing great white wines that are powerful, warm, while maintaining a high acidity, whether in dry or sweet white wine, sparkling wine, and of course, in vin jaune.

The flora itself

As Archestratus, a Greek poet from the 4th century BC, said, "This liquid appears covered with white flowers."

Preferably a "mouse skin" color, reflecting a gradient if the yeast population is diverse, and preferring transparency over thickness, unlike Sherry, the Jura voile is, in itself, a living ecosystem in autarky. Indeed, the yeasts feed on certain compounds in the wine, and over time, they become necrotrophic, ingesting the products of the decomposition of dead yeasts that have fallen to the bottom of the barrel – this is known as yeast autolysis. More specifically, some yeasts are broken down by their own enzymes and release various compounds (amino acids, peptides, polysaccharides, etc.) that are used by living yeasts to reform the voile. Over the 6 years of aging, a balance is established between dead and living yeasts, which allows for both the maintenance of the voile and the enrichment of the wine with flavors and aromas. We will return to this.

That said, at this stage, there is no explanation for why the yeasts rise to the surface of the wine. To resist the alcohol produced by alcoholic fermentation, yeasts produce fatty acids and modify the composition of their cell walls, increasing their hydrophobic character. For this, they synthesize new proteins (considered stress proteins) that allow them to bond together and form aggregates that trap the remaining CO2 in the wine: they rise to the surface, form islands of voile, and, upon contact with air, continue to multiply, eventually forming the famous yeast voile.

The effects of the flora

We do not say a "voile," but "voiles"

The aging process under the voile (veil) is not an exclusive feature of Vin Jaune and even less so of Château-Chalon. There are other wines produced with aging under flora. For example, certain Sherries made from Palomino, some Gaillac wines made from Mauzac, some Tokaji wines mainly made from Furmint, a Chinese rice wine called Jinfeng (also called huangjiu, literally "vin jaune"). But are these voile all identical? Is there not a voile unique to vin jaune, even to Château-Chalon? Here are some answers.

The sotolon molecule mentioned above actually exists in two enantiomeric forms, R and S (two isomers whose structural formulas are mirror images of each other). It turns out that the S form is 100 times more odorous than the R form. In vin jaune, the S form predominates, accounting for up to 75% of the total sotolon, while in rancios, for example, the ratio is reversed in favor of the R isomer. Therefore, the odor intensity of sotolon is much stronger in vin jaune than in a rancio. Other molecules also seem to distinguish vin jaune, but in a less significant way (solerone, pantolactone, dioxanes, and dioxolanes).

Another notable element of vin jaune is its fatness, roundness, or viscosity. This is surprising when we know that glycerol, which is partly responsible for the viscosity of the wine, is consumed by the veil yeasts during aging. It seems that this smoothness, almost sweet, is partly linked to the mannoproteins released during the autolysis of the yeasts – a phenomenon well known in Champagne, but still a hypothesis regarding vin jaune.

The acidity of Savagnin Blanc, as we have seen, is not unrelated to the higher concentrations of certain molecules, such as sotolon or 1,1-diethoxyethane, which enhance what is commonly called the "goût de jaune", but also the remarkable persistence of this taste at the finish.

Finally, the voile is primarily composed of Saccharomyces yeasts. It is not uncommon to find a dozen species in a Jura veil at the beginning of aging: Saccharomyces beticus, S. montuliensis, S. cheresiensis, and S. rouxii, along with other genera such as Hansenula, mycoderma, Candida, etc. That being said, it seems that the diversity of yeast strains decreases as aging progresses, leaving only one, often different from barrel to barrel. However, a freer progression of yeast strains at the start of aging is certainly more conducive to more complex wines, as is the case with alcoholic fermentation.

The yeasts of the voile are different from other oenological fermenting yeasts, even though they belong to the same family. They possess an additional gene, an adaptation to the environment allowing them to clump together and float on the surface of the liquid. And those in Jura are quite different from other identified veil yeasts elsewhere in other vineyards. While they appear similar to those found, for example, in Sherry wines, another wine "sous voile" produced in southern Spain, they differ by a deletion of 24 base pairs, which is a genetic mutation characterized by the loss of genetic material. Finally, and importantly, a comparison of yeasts within the Jura vineyard has shown that there are specific groups within the vineyards of Arbois and Château-Chalon...

Cellar, attic, or barn, storage places are a major influencing factor in the aging of vin jaune. Dry (favoring water evaporation and thus alcohol concentration, making the environment more resistant) and especially airy rooms are the most favorable for the development of the flora. Three elements should be considered: good air circulation around the barrel, low humidity, and seasonal variations more or less pronounced depending on the location:

Cellars: Often humid and poorly ventilated, alcohol tends to evaporate and weaken the wine.

Attics: Very dry and hot in summer, which leads to Château-Chalon wines that are often warm, concentrated, and less profitable due to high evaporation!

Barns: Dry, airy, and relatively temperate, they are very interesting for aging "sous voile".

That being said, blending several barrels from different places is often the best technique to produce wines that are complete, both powerful and fresh, intense and refined.

What might characterize Château-Chalon aging is the type of house called "mixed producer house." In the villages around Voiteur or Château-Chalon, on the limestone plateau, the cellars are semi-buried or built into a slope, with part facing outward. These architectural configurations, originally not designed for wine (but rather for storing foodstuffs and fuels), turn out to be a significant asset for aging "sous voile".

The "seven differences game" would be incomplete without mentioning the "terroir" of Château-Chalon. In tasting, compared to other vins jaunes, Château-Chalon expresses itself with power and balance. Understand "the right measure" between alcohol, acidity, and body. Never burning, never heavy, never acidic, Château-Chalon carries within it the harmony of great wines; a balance naturally acquired that flatters the tasting experience. Although often rich in alcohol, it seems, alongside other vins jaunes, the most slender, the most sharpened (a pH between 2.9 and 3.2 is not uncommon!). Often leaning towards citrus in youth, it gains in brilliance in its aromas, with this "penetrating" and "incisive" style that often characterizes the bouquet. On the palate, its generosity is caressing, if not silky. The finesse, or the thickness of the stroke that defines the sensations, is pushed to the extreme here. The length, finally, is remarkable. Château-Chalon resembles a very elongated cone, which points far at the finish, while its cousins are more cylindrical, built in width, which does not take away from their charm.

To justify these observations, some call upon the terroir, which is characterized, among other things, by a more delayed mesoclimate than that of Arbois, for example. And of course, the gray marls of the Lias, which would almost justify the unique profile of the wines by themselves. While there are undeniably geochemical characteristics specific to the Château-Chalon vineyard, the influence of the producer, both in their choices and by their environment, remains decisive in the expression of the wines (Study of soil-grape relations in the Jura vineyard: example of the Trousseau grape variety in the Montigny-Lès-Arsures terroir – Leveque et al., 2006; Scarponi et al., 1982; Asselin et al., 1983; Maarse et al., 1987; Moret et al., 1994; Day et al., 1995b; Sauvage et al., 2002). And in Château-Chalon, the human influence should not be underestimated. The culture of great wine is often, if not always, deeply rooted in history and remarkably sedentary. Laudatory testimonials about Château-Chalon wines abound and date back to the 18th century for the oldest ones. Even today, despite the vicissitudes of vineyard life, Château-Chalon carries the image of a great wine among enthusiasts who may have never tasted it! Although clearly, not all Château-Chalon wines are the same, the historical culture of great wine permeates customs and practices, requiring a minimum of commitment and responsibility from the producers who inherit this appellation.

In the end, perhaps it is all of this that makes Château-Chalon unique. A blend of culture, history, geology, relief, architecture, science, yeasts, and men and women who, attached to their land, maintain the image of the greatest of vin jaune..

Conclusion: Praise of the hedge

Reading Sonia Feertchak's magnificent book L'éloge de la haie (The Praise of the Hedge), I couldn't help but draw a parallel between the hedgerows of our countryside and the flora of vin jaune, especially that of Château-Chalon. This bold comparison can make sense if we focus on the simple idea of a boundary between two spaces. The hedge as a boundary, the wine and the air as the flora. But Sonia Feertchak takes this much further. She invites us inside and beyond the hedge, making our comparison a much richer, kaleidoscopic journey.

Let’s listen to anthropologist Tim Ingold, cited in this book, as he talks about the hedge: “In this entangled zone – a mesh of interwoven lines – there is neither inside nor outside, only openings and passages” (A Brief History of Lines, Sensitive Zones, 2013). It is, therefore, a porous boundary that constantly evolves and reshapes both space and time. How can we not see this as an allegory for the veil? This entangled flora, both alive and still, that changes its composition according to time, but also depending on the space it occupies within each barrel. This flora that feeds on both the air and the wine, disregarding the distinctions between the outside and the inside. Finally, this flora that both lets things pass and simultaneously resists. If there is one place where separation does not happen, it is within the flora. Its thickness, which is very fine, is not resistance, but adaptation to the environment. As Sonia Feertchak reminds us: “The hedge (the veil) puts under our nose its fourfold status: meeting place, nursery, refuge, larder…”. Everything is said.

The hedge and the flora are “clean dirt,” to borrow Marc-André Selosse’s phrase. There is no question of them being artificial, or they lose their “substantive essence,” as Rabelais reminds us. However, as major actors in the continuity of life, they must persist. Paul Valéry said: “Two dangers continually threaten the world: order and disorder.” Let’s settle this: the flora is a disorder with balance. It is syntropic. And thus remarkably modern (syntropic agriculture is very close to permaculture and agroforestry...).

If the flora is not a limit, and it is not an artificial construction, it forces us to rethink certain long-established oppositions, sometimes clumsy ones: outside and inside, order and disorder, cleanliness and dirt, as we’ve seen. Let’s continue: wild and domestic, art and science, nature and culture (let’s reread Descola). The veil is the place where we learn to rename things, to distribute continuity and discontinuity differently. Who has not heard that vin jaune is an oxidized wine? A dead wine? When, on the contrary, it is a celebration of life, an aesthetic project triumphing over oenological standards.

If the flora is not a limit, it does have one, that of its power or action. Gilles Deleuze uses the example of the forest. I quote the philosopher, also from Sonia Feertchak’s book: “The forest is not defined by a form [‘the boundary contour’], it is defined by a power: the power to grow trees until it can no longer.” Just after: “The thing is therefore power and not form.” We are there. The veil, that of Château-Chalon, does not find its limit in the barrel, but in its power. In other words, in its capacity to colonize the cellars and proliferate in the vineyard. The reverse is also true: if this Château-Chalon veil, whose uniqueness no longer needs demonstrating, exists in the barrel, it is because the entire vineyard (from the grey Lias marls to the rock cellars through to the Savagnin blanc) gives it the possibility to exist. In this way, and against all expectations, the flora is the tangible, material, and living proof of the existence of terroir, particularly that so singular and marvelous of Château-Chalon. The last word goes to Bruno Latour (Face to Gaia, Ed. La Découverte): “It is about not taking away from the Earth the powers to act that it possesses.”

Olivier Borneuf

Our Selection from the Great Tasting (the wines were not tasted blind, and not all producers were represented in every vintage. Sometimes only one wine was present in a given year).

Domaine Courbet – Sous roche 2016: A wine of higher concentration for the vintage, hesitating between floral, vanilla, and fresh walnut, with an airy sap, long, "chalky," and saline, with great purity. 94

Fruitière vinicole de Voiteur 2016: Balanced, waxy, clean, with a spicy fruit note reminiscent of ginger. 90

Domaine Désiré Petit 2016: Delicate yet firm. Excellent freshness on the finish, leaning on citrus fruits. 92

Domaine Rolet 2016: With citrus zest, medium-bodied, but precise and balanced. A good wine. 92

Domaine Berthet-Bondet 2016: Good volume, clean, with a pastry-like base, finish on green almond and a hint of saltiness. A beautiful wine. 93

Domaine des Carlines 2016: Original, slightly smoky, stylized, with a finish that is a bit soft but flavorful. 91

Domaine Grand – En Beaumont 2016: Rich nose, creamy, generous mouthfeel, long, flavorful, tactile, and saline finish. A caress. 93

Domaine Macle 2015: Pure, floral, and citrusy, with remarkable length, returning to a characteristic "green fruit" freshness. A great wine. 97-98

Fruitière vinicole de Voiteur 2011: Just creamy, evolving with curry and fresh walnut notes. Pleasant and balanced today. 90

Domaine Macle 2009: Pure, evolving with orange peel, then mineral. Smooth finish, almost pastry-like, always balanced, ending with saline and chalky sensations. A beautiful wine. 97

Domaine Berthet-Bondet 2009: Generous, hesitating between pastry and bitter orange, then curry, with a finish almost chalky. A lovely wine. 93

Caveau des Byards 2004: Old-fashioned charm, gourmand and still retaining fruit, balanced finish. 90

Domaine Rodet 2002: Clean, consistent, playing between citrus and pastry, then green walnut in a delicate and precise finish. A beautiful wine. 94

Domaine Désiré Petit 1992: Austere profile, consistent, very nutty, but clean and sharp. 91

Domaine Courbet 1988: Beautiful length, spicy and consistent texture. Great evolution. 93

Domaine Macle 1988: After a Burgundy-like toastiness, with candied citrus, pastry notes, both gourmand and delicate, endless finish, wavering between ginger, iodine, and chalk. Superb. 98

Fruitière vinicole de Voiteur 1985: Forest floor, pastry, bold and punchy texture for the vintage. 92

Fruitière vinicole de Voiteur 1964: Remarkably fresh and clean after 60 years in the bottle! Not notable.