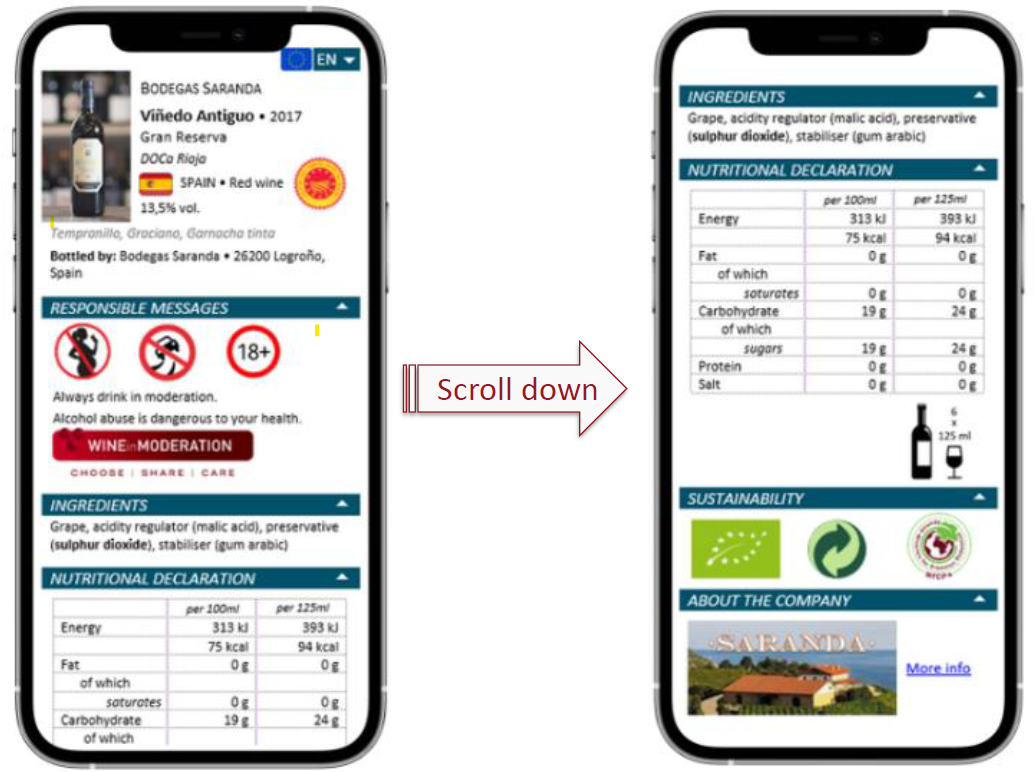

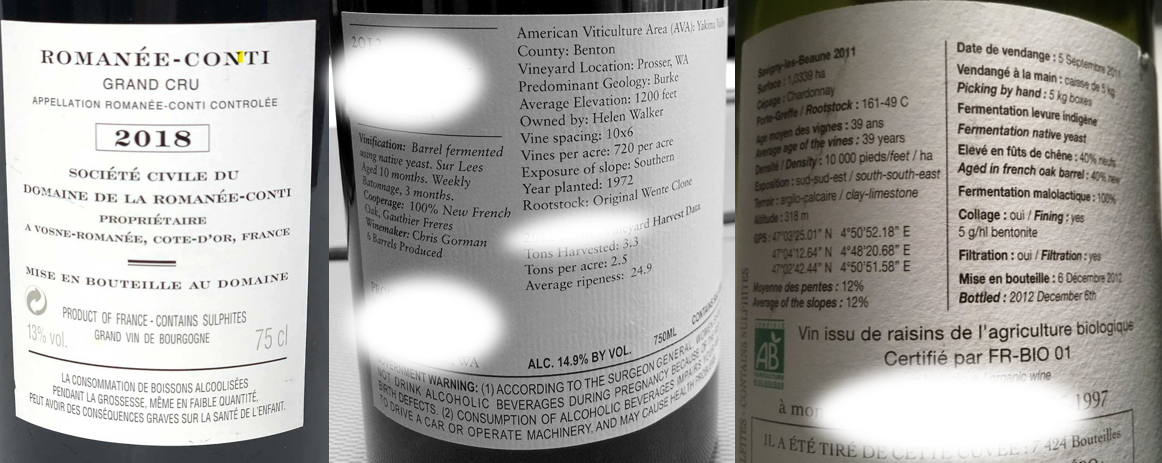

When the bottle speaks to us... Or, more precisely, when the containing speaks to us about the content - from environmental and quality labels, to sulfite-free logo and other technical information, to nutritional values and a list of ingredients - we have to recognize that both legislators and producers have a zealous, if not populist, desire to demonstrate transparency, both in terms of health and the environment.

The question arises, however, as to whether the containing, by dint of wanting to talk about the content, has not simply substituted itself for the latter, making its accoutrements - personalized label, sulfite-free stamp, Qrcode or back label acting as a technical data sheet - a content in its own right? Perhaps it would be a good idea to ask the content what it thinks of the containing!

Here are two questions the content could have asked: what does the wine taste like? Isn't it the one thing that's been left out of our ultra-informed containing? Second question: does the consumer understand? Can they act on this information? In this case, isn't the best the enemy of the good?

The question of enlightened consumer knowledge, correlated with the more complex one of a culture of taste, places the wine producer at the heart of a contradictory communication and pedagogy. Accused a little too quickly of standardizing the taste of wine with figures and standards, recipes and protocols, modern oenology has seen its own analytical tools confiscated in favor of a virtuous containing, which has become a force for consumer emancipation. The apparent accuracy of sulfite levels, the deliberate scientification of the back label, the soothing virtues of a standard or a label play oenology and the winemaker at their own game: depriving the consumer of his capacity for imagination and idealization, in other words, his capacity for sensitivity.

This rhetorical pirouette, which turns the defenders of transparency into zealots for an arch-rationalized authenticity in which the consumer is corrupted, is in fact nothing new. In his 1859 Salon, the French poet Charles Baudelaire, criticizing the artists known as realists or naturalists (any resemblance to certain wine movements is obviously coincidental!), said that "artists who wish to express nature minus the feelings it inspires are subjecting themselves to a bizarre operation which consists in killing the thinking and feeling man within them." What does this mean? That these naturalist artists, whom Baudelaire renames positivists, are unwilling participants in the archirationalization of the world, sacrificing their capacity for imagination on the altar of transparency and "naturalness", which I like to put in quotation marks.

Oenology is a science of the living in the service of an aesthetic project. Whatever the values that have historically accompanied wine - health or social representation, for example - aesthetic prevalence is omnipresent. Reconsidering oenology in its most fundamental, not to say most aesthetic, definition gives it a chance to appear in a refreshing light to new consumers: the containing as an extension, or rather an aesthetic prologue, to the content. Some producers have already understood this, gracing us with refined packaging without technical fuss.

But before we get out of the bottle, we have to validate the idea that oenology can be, dare I say it, beautiful from the inside out. I'm not saying that we should burst into tears following a spasm of aesthetic aftershock caused by the end of alcoholic fermentation. No, let's rather say that the producer, whether winemaker or oenologist, is not necessarily a skinned man endowed by divine grace with a superior sense of beauty, nor is he the cold individual with a flat electroencephalogram who spends his life in front of Bunsen burners. Rather, let's say that the producer, like the artist, also feeds on the sensitive, without necessarily converging towards the same goals. In fact, I'd argue the opposite! It's this tension between aesthetics and science that makes oenology so fertile and, ultimately, alive. For Bertold Brecht, in a 1945 text entitled The Purchase of Copper, I quote: "People who understand nothing of art or science believe that these are two immensely different things, of which they know nothing. They imagine they are doing science a service by allowing it to be unimaginative, and they believe they are advancing art by preventing anyone from expecting intelligence from it. A man may have a particular gift for a particular discipline, but he is not all the more gifted in that discipline as he is more incapable in all the others. Even if humanity has long and often had to do without knowledge as well as art, the fact remains that both are essential to what we consider to be "human". No one is totally devoid of knowledge, and no one is totally devoid of art.

Consumers love demagogues and populists, but they prefer to listen to the scientist if the latter takes the trouble to explain. Has the wine industry done this? I think the answer is no. And what have we said about taste? Not much. We never asked ourselves “from where” we were talking about, to use Pierre Bourdieu's famous phrase. Because when we talk about taste, it's disgust we're talking about, disgust at the taste of others, those who are not wine producers or, more generally, wine professionals. If the producer is the man-who-knows, he must be the scientist-pedagogue who popularizes the indisputable knowledge of oenology. If the term "sulfite-free" makes us jump at the nonsense it conveys and the posturing it engenders, we must first blame ourselves! On the other hand, if the producer is the wine lover, he must also be the enthusiast who describes the wine with lyricism and subjectivity. It's an ambivalence with porous boundaries, yet it defines precisely what the producer, with his science and passion, represents in all his humanity, and should convey on his bottles.

Let's not let demagogues use the dictatorship of numbers to replace taste with values and science with dogma. Knowledge and lyricism are not opposites, but asymptotics. Let's turn the containing into a new content, with pedagogy, passion, humor and, above all, honesty.

Olivier Borneuf