The grass is always greener on the other side of the fence. This sums up well the anecdote recounted by the director of a Classified Growth (GCC in French: Grand Cru Classé) in 1855, during our visit to Médoc and Sauternais for the tasting of the 2020 and 2021 vintages* at the beginning of February. An anecdote that, according to him, determined his career. Young and ambitious, this freshly graduated oenologist then dreams of California. Attracted by the dynamism and modernity of Napa Valley wines, he meets producers surprised by the enthusiasm of the young man for American wines: "The whole world dreams of vinifying a Grand Cru Classé from Médoc and you come looking for work with us!" From across the Atlantic, the grass was obviously greener in Médoc (although at the time, grass was scarce...). It was also for "the whole world"... That was enough to convince our dear oenologist to return to France and continue his brilliant career within a GCC in Médoc.

Do you know many wines that "the whole world" would dream of producing? One might be tempted to mention quite a few, but the reality is much clearer: the Grands Crus Classés of Bordeaux and the Grands Crus of Burgundy overshadow the competition beyond our borders... However, the GCCs, with the exception of a handful of châteaux, acknowledge that the current market is hard. As evidence, the mixed results of the last En Primeur campaign on the excellent 2022 vintage. Between facts and words, there are the ailments that many believe to have identified: prices, image, quality, distribution, etc. Everything is discussed without a clear understanding of the state of the Grands Crus Classés market. We take the risk ourselves, not without a certain detachment, by critiquing not the châteaux, but those who have spoken about them, to better reveal what has not been said or understood, and to justify our analysis of the 2020 and 2021 vintages.

The negative effects of benevolent wine critics

As critics, we obviously have a well-founded analysis of the evolution of wine quality. As critics, we also have a view of our colleagues, always benevolent, but always sharp! If the press has no power, that is, a command position that would lead its readers to do what it wants them to do, it nonetheless remains influential in its capacity to modify the representations and behaviors of the latter.

Specialized press, and more particularly wine critics, have played, in their majority, an underestimated role in the current perception of GCCs. Their interested benevolence towards certain châteaux, regardless of the vintages, has had deleterious consequences on the contemporary amateur. If the Châteaux have an interest in obtaining the highest rating, the critic also has an interest in giving the highest rating, in order to benefit from the symbolic and material resources of these same châteaux.** Ultimately, if these latter highlight those who appreciated them, it's fair game! All wine producers on the planet do this. Since the rating creates value, it's better to take the highest ones - business is business. But when all the critics unanimously or nearly unanimously support the unbearable, a very bad vintage for example, repeatedly, year after year, things get complicated. Critics may try to perform acrobatics like "in absolute terms it's a good rating, but for this château it's a bad rating", but it's too late, the amateur no longer believes it, the châteaux disconnect from reality, delay efforts to provide if necessary, and hasten the decline of their wines through the ratings they believe serve to valorize them.

However, once the correct diagnosis is established and major projects are undertaken, the difficulties persist. And for good reason: it's always the same, those whom the amateur no longer believes, who ensure the media coverage, making their publications the worst of advertisements. The best proof is the exceptional succession of great vintages that Bordeaux has experienced in recent years, without experiencing equivalent enthusiasm in the markets. The issue of price so often advanced is actually an unfortunate consequence that adds fuel to the media fire; the most expensive wines being those that sell the best. As for wine volumes, this is more about transferring to other regions with a more attractive image than a world decrease in consumption that is certainly real, but not yet significant enough. And quality? We're getting to that.

The destructive banalities of sensationalist press

Mainstream media, on the other hand, has been responsible for disconnecting the image of wine from the wine itself, remaining silent on the qualitative evolutions of the region in favor of a accumulation of scandals of all kinds. From the vineyard to the cellar, including consultants, everyone has been criticized! It would have been journalistically rigorous to extend these investigations to other regions (and not just Champagne, the eternal accomplice of Bordeaux, as is well known) for a more objective perspective on the state of French wine industry. On this point, we will simply recall that the grass, thirty years ago, was not greener elsewhere. Productive clones and rootstocks, for example, were the norm everywhere in France in the 1980s. Just like herbicides and nitrogen fertilizers. With the exception of a few avant-garde producers here and there, the entire French vineyard, at that time, experienced high yields and sugar ripeness at the expense of fruit. As for winemaking, don't imagine that Bordeaux oenology was less virtuous or more interventionist than elsewhere! And as for wine consultants, while some in Bordeaux have become famous, those located in other regions have had just as much influence, but certainly less media attention.

In reality, as early as the 2000s, Bordeaux initiated changes in its vineyard culture and winemaking practices. And for the past fifteen years, a significant number of châteaux have maintained vegetative cover between the vine rows, both for soil water management and for nitrogen fixation and soil loosening. Replanting has taken place, prioritizing massal selections and higher quality rootstocks. Similarly, the planting of grape varieties has been reconsidered based on quality (previously, many châteaux protected Merlot, known for its early budding, by planting it in frost-protected gravelly terraces, despite these being considered ideal for Cabernet), as well as row orientation to mitigate the effects of climate change. Despite an oceanic climate conducive to the development of fungal diseases, alternative viticultural practices such as agroforestry or organic-biodynamic agriculture have emerged within the vineyard. In the cellar, grapes arrive ripe, not overly ripe or underripe. Tanks have multiplied to take advantage of parcel vinifications or vine age vinification. Whether it's optical, density-based, or visual sorting at harvest, spaced-out pump-overs, or the use of Rpulse*** technology during the fermentation phase, winemaking techniques have evolved dramatically on a raw material often better preserved at the time of picking.

Regarding wine aging, it has become more refined, sometimes shortened, in favor of better-selected oak and alternative containers such as dolia, large wooden vats, or Wineglobes, limiting the risks of oxidation and excessive oak influence. Finally, microbiology has also evolved. While the 1990s and 2000s left some unhappy memories of "bretty" wines, as in other regions, recent vintages seem to demonstrate greater precision in this regard even as climate change makes wines more vulnerable.

All things considered, the press, lacking in information, has preferred to create sensation, favoring in its articles the name of the architect who redesigned the cellar at the expense of the viticultural and oenological changes that have put the châteaux back on the path to quality. It's a shame because there was truly something to criticize about the wines of yesteryears, yet they were highly rated by critics, these wines that partly disappoint today because they are already evolved or dried out by oak. It's a pity because it would have allowed these châteaux to talk about their projects, their thoughts, and their desire to move towards more balanced wines, which they have been producing for about ten years now. The press could have informed the wine lover, and the wine lover would surely have forgiven.

Bordeaux, the sounding board of French viticulture

Ultimately, if Bordeaux has been in the spotlight, it is mainly because Bordeaux and its Classified Growths crystallize debates. All the ingredients of a soap opera are there for our eyes: the great estates, the great patrons, the great consultants, political scandals, ecological scandals, and so on. Let's not forget that this juicy news is also the lot of other French wine regions. It is simply less embodied and certainly less known to the general public. Of course, Bordeaux is not free from criticism (who is, anyway!), but what applies to the region also applies to others, to varying degrees depending on the topics discussed. It's amusing to note that wine lovers often know the owners of Château Latour and Château d'Yquem but are unaware of those of Clos des Lambrays or Clos de Tart in Burgundy... As if the virtue of investment depended on the vineyard! Let's add one last element, size: an average of 19 hectares of vineyards per producers in France, 6.50 hectares in Burgundy, 17 hectares in Bordeaux, and 70 hectares for the Grands Crus Classés in 1855. It is evident that a vineyard in Burgundy and a GCC in the Médoc or Sauternes are not managed in the same way. This partly explains why the GCCs seem less susceptible to trends, which are by definition ephemeral, than to lasting trends: here, changes are not made on a whim but out of conviction.

The "composite Bordeaux" has triumphed over the "Bordeaux style"

The latest vintages in bottles are 2020 and 2021. A comparison rich in lessons as it forced châteaux to reveal themselves in extremes. On one hand, 2021, characterized by spring rains and a dreary summer (followed by a late but significant summer drought), which required restraint in skin extractions. On the other hand, 2020, marked by a hot spring and a very long period of drought without a drop of rain (saved by cool September nights), which demanded great attention due to very concentrated grapes (with record TPI**** values). Few châteaux succeeded in one vintage and failed in the other. This suggests that a château's success relies less on quality than on style. The restraint required in 2021 was essentially the same as that needed in 2020 for opposite reasons. Châteaux that shone with delicacy and balance in 2021 magnified the powerful 2020s with a refined and silky touch, with powdery tannins. Another notable fact is the brightness of the fruit in both years. With few exceptions, 2021 displays a vibrant profile while 2020 shines with its perfect ripeness. On both sides, for opposite yet perfectly symmetrical reasons, aromatic expression reveals precision and brilliance, auguring well for the future and confirming, if necessary, the excellent progress in aging and oxygen management. One last noteworthy fact is the increase in Merlot percentage in 2020 compared to 2021. We can readily interpret this as a sign of the paradigm shift in agronomy explained earlier, one of better soil-grape alignment, with, where applicable, better-selected plant material. The overripe Merlot, compensating for a rarely ripe Cabernet, is replaced by a more harmonious and differential Cabernet-Merlot complementarity.

At Margaux, Château Brane-Cantenac leads the discussions on both vintages in a style worthy of a "First Growth." Châteaux Cantenac-Brown and Marquis de Terme are ones to watch closely, with wines gaining in elegance and precision. Finally, Château Marquis d'Alesme, in 2021, is a pleasant surprise, seeing its efforts rewarded. In Pauillac, Pontet-Canet remains as refined as ever, perhaps with a sense of regained precision. A standout is Château Pédesclaux, very elegant, showcasing impressive work done. Château Lynch-Bages stays true to itself, impressive, but with added precision this time. In Saint-Estèphe, Château Montrose 2021 captivates with its delicate style, while Tronquoy 2020 delights and surprises, as always. Lastly, in Saint-Julien: Château Léoville-Poyferré remains concentrated but better defined, hence more balanced, which is commendable. Château Talbot seeks harmony and finds it, sounding just right and pleasing. Similarly, Branaire-Ducru, with a restrained and consistently balanced style, if not elegant. Regarding Graves, let's not forget La Mission Haut-Brion and Château Haut-Brion, which have become lace-makers in 2021 (imagine Chambolle-Musigny Les Amoureuses in Cabernet-Merlot version...). The 2020s are equally remarkable but diametrically opposed, with a voluptuous Mission and an abyssal Haut-Brion.

On the sweet wine side, Barsac and Sauternes confirm the stylistic changes initiated over 10 years ago, namely shorter aging, better control of juice oxydation, and an accepted portion of "raisins dorés" (overripe but not botrytised grapes) that in no way diminishes the remarkable complexity of these great wines. 2021 was very challenging in Barsac, heavily hit by frost, and very low yielded in Sauternes. Multiple tries for a few hl/ha (1hl/ha at Château Coutet!), drastic selections to avoid sour rot, resulting in rare wines of excellent quality, bright and citrusy in aroma, with excellent freshness. The precise and lively style of the vintage makes them very enjoyable to taste already. Among those who managed to produce some bottles, Château de Rayne-Vigneau, Château Coutet, and Château Suduiraut stand out for their purity and freshness. As for 2020, it presented challenges, with a series of rainy episodes starting from late September, forcing châteaux to choose between harvesting low-sugar concentration grapes or taking the risk of waiting to see their boldness rewarded. Again, low yields (8.5hl/ha at Château Suduiraut) for wines of high quality, more exotic and ample than in 2021, but hardly richer in sugars, with the interesting characteristic of being very pleasant to savor today. Château Doisy-Védrines, Château de Myrat, Château Guiraud, Château Coutet, and Château Suduiraut are the winners of the vintage.

The few dry whites we had the opportunity to taste are very relevant. In the stylistic continuity of the reds, the aging is subdued in favor of a more straightforward and less varietal fruit. The balances lean towards a more streamlined and less demonstrative style, which we prefer, especially in the underrated 2021 vintage – whereas many favored a more flattering 2020. In this regard, let's salute the great 2021 whites from Clarence Dillon: Clarté de Haut-Brion, La Mission Haut-Brion, and Château Haut-Brion, all absolutely brilliant in this slender and limpid style. Further south, the remarkable Opalie from Château Coutet, still in 2021, is delicate and saline, like a nod to its sweet cousin.

All the wines tasted can be found at the end of the article for a more detailed review of the vintages. If there is one key takeaway from these tastings, it is that of a "Bordeaux style" that is now a thing of the past, one that once allowed anyone to identify Bordeaux and, unfortunately in recent years, has become synonymous with all the criticisms of the contemporary wine enthusiast due to inertia. This style has given way to a "composite Bordeaux," whose expression is diverse and always unique. In this "composite Bordeaux," the wines share a common thread. This thread is not an oenological style, but rather a common feature resulting from a tension of opposites... Many vineyards cultivate Cabernets and Merlot. But which ones achieve concentration and freshness, complexity and finesse, structure and harmony in the same wine? It starts with a B.

Olivier Borneuf

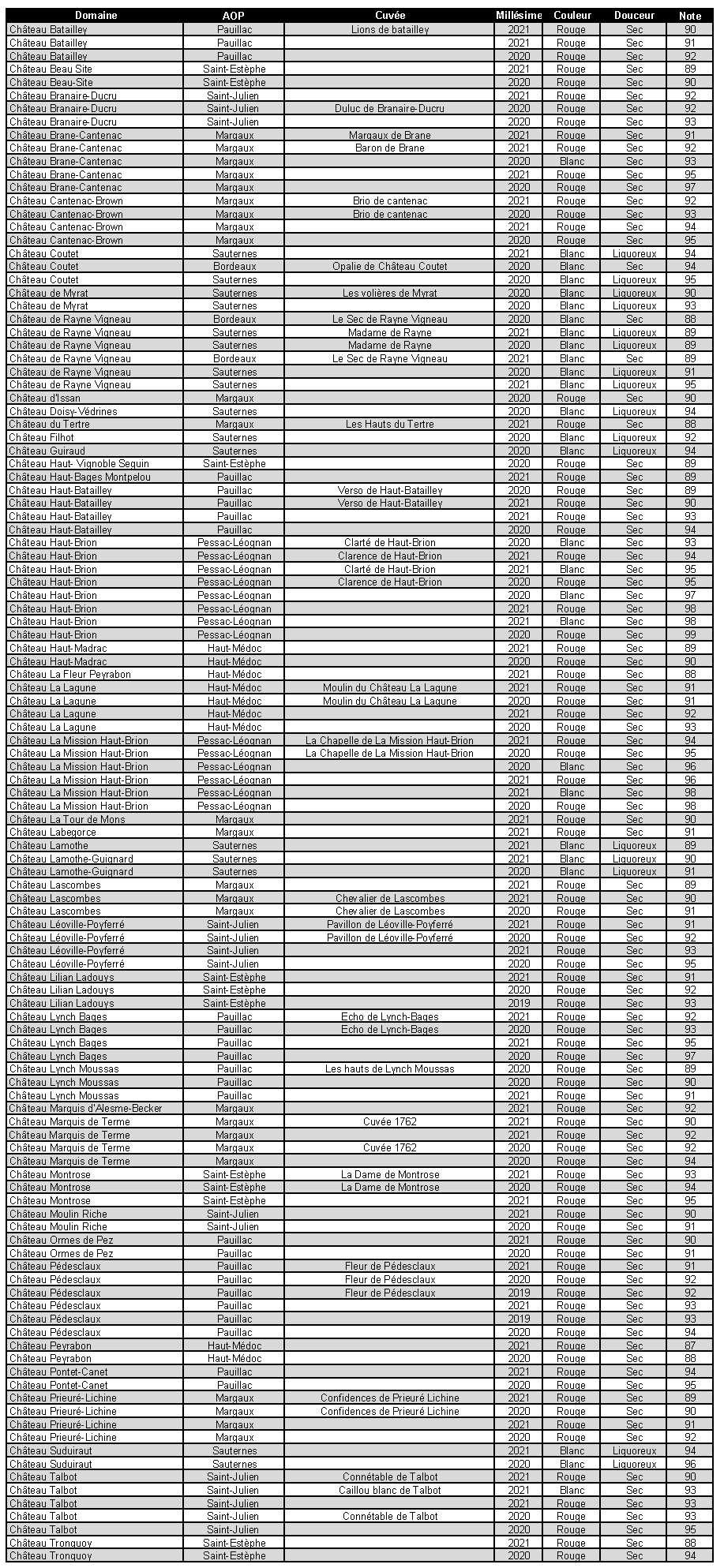

*The tasting of the 2020 and 2021 Grands Crus Classés in 1855 wines was organized by the Council of Grands Crus Classés in 1855. Our thanks to its President Mr. Philippe Castéja and its director Mr. Sylvain Boivert for the organization.

**If the Château has an interest in obtaining the highest possible score, what is the critic's interest in giving a better score? If the critic "disappoints" the Château, their score may not be considered by the latter, resulting in a loss of visibility for the critic in the media world of fine wines. On the other hand, if the critic praises the same Château, it is likely that their review will be included in the Château's publications. Furthermore, the critic may decide to "follow" the average score of their colleagues in order not to be excluded from the media sphere to which they need to belong to exist. In other words, a critic may secretly disagree with the general trend on a wine, and publicly decide to join the majority, especially if this critic maintains commercial relationships with the Château.

***Used by many Châteaux since 2018, the Rpulse technology delicately renews the marc cap during vinification without mechanical action.

****Total Polyphenol Index